Helen Forrester: Tuppence to Cross the Mersey and Liverpool Miss.

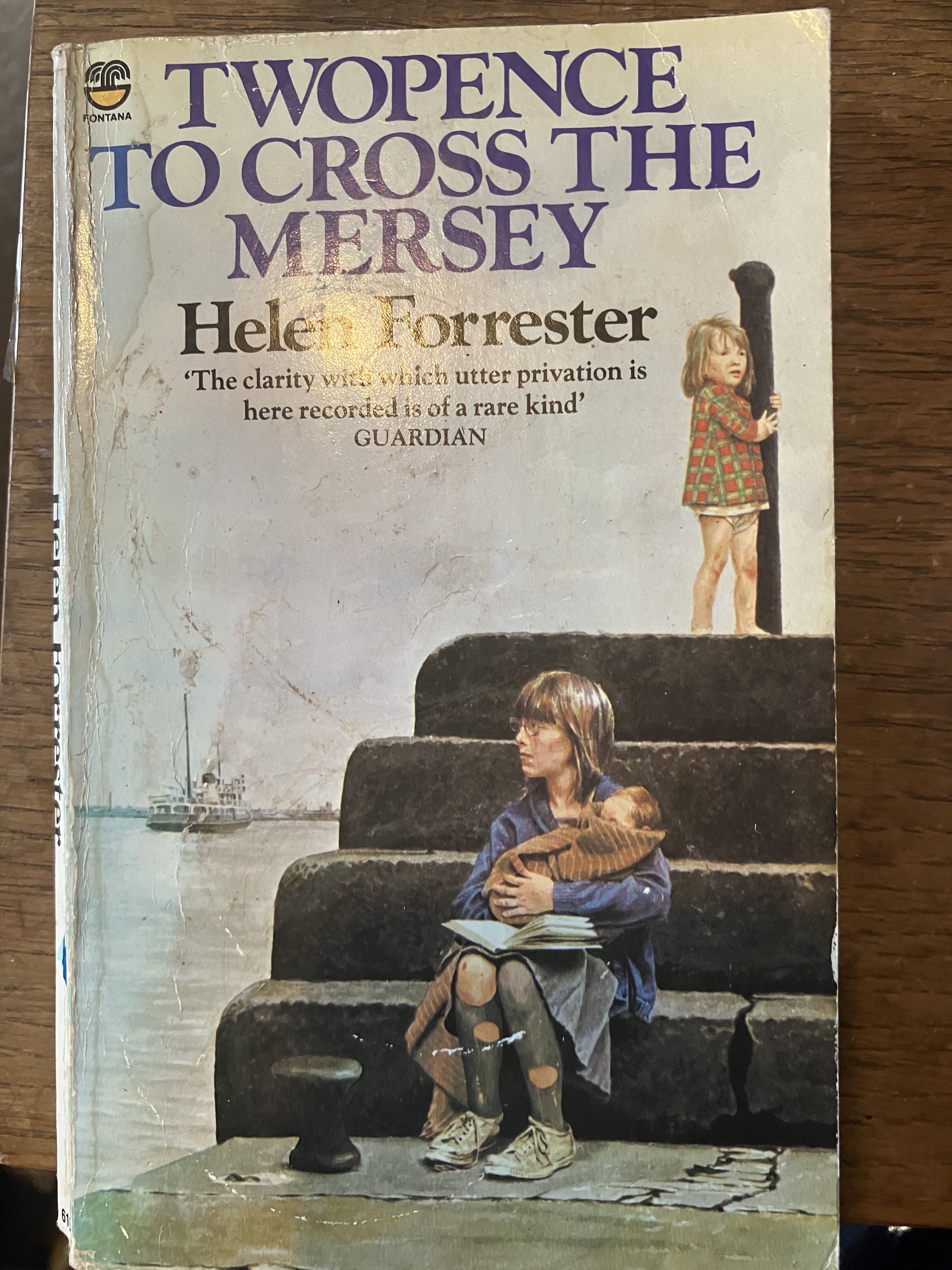

Helen Forrester (1919-2011) is one of the best-known memoirists to chart working-class life in twentieth century Britain. In some ways she is atypical, having suffered a dramatic fall into poverty after being born into a relatively prosperous (if profligate) upper-middle class family. However, I will outline some of the reasons why I have found her memoirs to be particularly fruitful. As hers was one of the first working-class memoirs I ever read and particularly having grown up in Birkenhead, her books retain an especial significance in my own work and historical practice. Here, I focus on her first two memoirs – Twopence to Cross the Mersey and Liverpool Miss – and will return to her subsequent books in a later post. Born June Huband in Hoylake, Helen was the eldest of seven children to upper-middle class parents. Her home life was extremely fraught due to her parents’ violently tempestuous marriage and the impact of the traumas her father had experienced in the First World War. The most significant moment in Helen’s life occurred when her father went bankrupt and lost his job as a bank clerk in 1930, following a long period of reckless spending and financial mismanagement. Encapsulating her parents’ financial naivety, her father decided that moving to Liverpool would ensure the best opportunity for the family to regain their prosperity. Helen’s first and best-known volume of her memoirs, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, described the family’s arrival into Liverpool January 1931 when she was aged 12, where they found a city ‘which seemed to be slowly dying.’[1] Her moving account of the poverty and hardship the family faced highlighted the devastating impact of the interwar economic depression on cities like Liverpool and helped to shape a genre of working-class writings by authors born at a similar time.

Helen wrote four volumes of memoirs during the 1970s and 1980s covering around fifteen years of her life, from the family’s arrival in Liverpool in 1931 to the end of the Second World War. Her memoirs do not cover her later life, but we know that in 1949 she met and fell in love with Avadh Bhatia, a PhD student. Avadh returned in India in March 1950, Helen joined him the following year and they married and had one son, Robert Bhatia. In 1955 they moved to Canada where Avadh worked as a theoretical physicist the University of Alberta. Helen became a successful novelist: her works such as Thursday’s Child and The Moneylenders of Shahpur are strongly influenced by her life in India whereas Liverpool Daisy and Three Women of Liverpool are set in the poverty-stricken areas of Liverpool that she had experienced in her youth. Helen was moved to write her memoirs whist working on her fourth novel in the late 1960s, following an interview she did with by a Canadian journalist who described Helen as a ‘sheltered little professor’s wife sitting amid her priceless English teacups.’ Helen later wrote that she was ‘terribly, terribly angry’ and abandoned the novel she was working on and instead wrote Twopence to Cross the Mersey ‘in total rage.’[2]

Twopence to Cross the Mersey was rejected by ten publishers, as editors objected to its lack of humour and disbelieved the level of deprivation the book depicted.[3] It was finally published in 1974 but only found success when it was reissued in 1979, when it became widely loved and was turned into a musical in 1994. It remains especially powerful in describing urban working-class life in depth and detail whilst avoiding overly nostalgic cliches of togetherness and communal self-sacrifice that so often underpin popular depictions of the early twentieth century. One theme that comes across is the scant support for those in need and the absence of state welfare as we know it, particularly the lack of free medical care or help for poor families. We share her father’s sense of shock and disbelief when, shortly after arriving in Liverpool, a priest encouraged the family to apply for Poor Relief, he explained:

“Well, it is really the old poor-law relief for the destitute, but it is now administered by the city through the publication assistance committee. More help is given by way of allowances rather than by committal to the workhouse.” Father went white at the mention of the workhouse, I stared in shock horror at the priest. I had read all of Charles Dickens books – I knew about workhouses.[4]

It is sometimes difficult to believe that the workhouse system still existed at such point in the twentieth century and Helen’s account reminds us of the enduring shame attached to poverty, the absence of support for those in need, and the sheer horror of becoming destitute. Helen’s reflective and critical approach towards her parents, the authorities, the poor, and herself, that makes her accounts particularly fruitful. Helen’s inverted Cinderella story – the middle-class girl dropped into the Northern slums – has almost become folklore in itself, but returning to her memoirs has been invaluable to me in thinking about how those (and particularly women and children) who lived in the kinds of urban neighbourhoods that Helen depicts understood important notions of belonging and deviance. Her work reveals the kinds of tensions and clashes that arose between the poor and the authorities, as well as crucial methods of evasion against the invasive and cruel policies subjected to those in poverty.

Twopence to Cross the Mersey introduces us to Helen and her family in the aftermath of her father’s bankruptcy and as her mother was recovering from the birth of her seventh child and an emergency hysterectomy. Perhaps it was naivety, panic or misplaced confidence that led her father to move the entire family from Nottingham to Liverpool, where he thought he could turn his fortunes around. Helen described waiting in Lime Street station with her sister and brothers, whilst her father looked for work and housing and her mother lay in the station waiting room recovering from major surgery: ‘I had no conception of the panic gripping my parents, a panic which had made them lose completely any sense of proportion. They had been brought up in a little world of moneyed people, insulated by their private means from any real difficulties or hardships. When there was no money, they had no idea what to do.’[5] They had arrived in a city where unemployment was twice as high than the national average and one of the highest rates of poor relief in the country. Not only was it virtually impossible for her father to find work, but he could not claim dole having not paid into the insurance scheme and was only eligible for public assistance paid at the lower rate of the small town they had been residing. Unable to claim the higher rate of assistance for Liverpool, which also included extra payments for winter coal and at Christmas, the family was plunged into dire poverty exacerbated by the continued poor financial decisions made by her parents. They moved into overpriced, overcrowded rented rooms where they narrowly avoid starvation. Helen showed that her parents never really grasped the importance of money management and were prone to purchasing expensive furniture on hire purchase – even when the children did not have beds or adequate bedding. It was only following the intervention of a doctor after Helen experienced a severe case of influenza and he noted her extreme malnourishment, did her mother really start to prioritise spending on food.

It is perhaps Helen’s status as an outsider that makes her accounts of life in Liverpool in the 1930s and 1940s so striking and impactful. In some ways, her middle-class background comes through in her writings and she acknowledges the horror she felt at being removed from her comfortable home: ‘God, how I had minded the dirt! How terrified I had been! How menacingly grotesque the people had looked; children of the industrial revolution, nurtured for generations on poor food in smoke-laden air, grim and twisted, foul-mouthed and coarse… And I, a middle-class girl of the gentler south-west of England who had been shielded from the rougher side of life…. I had been thrown among them.’[6] Similarly, in the second volume of her memoirs, Liverpool Miss, she complained that the girls in her neighbourhood ‘seemed hardly human… they gawked and giggled and shrieked at the gangling youths hanging uneasily about the street corners.’[7] I find this perspective particularly helpful in dispelling some of the myths of life in urban working-class neighbourhoods, which often emphasise a sense of togetherness and of close-knit bonds, without explaining or acknowledging that the implications of these ties meant that they were hostile or difficult for those deemed to be outliers. For example, Helen describes the bullying she and her sister Avril experienced at the hands of local boys who also targeted a girl who was the daughter of a Black medical student and a young boy with disabilities, who both lived nearby. Helena explained, ‘None of us was human by the standards of these lads – we looked different – and we ranked with dogs and cats, to be teased and mishandled if caught.’[4] Although these kinds of recollections are difficult for readers, it is important to avoid allowing nostalgia for the past to overlook the very negative and problematic aspects of life in these neighbourhoods because they help explain wider forms of exclusion, discrimination, and social tensions. It also provides an opportunity for Helen to defend those suffering from poverty, particularly through her work as an office girl for the Liverpool Personal Services Society, a small welfare charity in Bootle, shortly after turning fourteen. She wrote, ‘In large areas of Liverpool there was barely an inhabitant who was not in distress. Workless, half-starved, they were packed into deteriorating houses lacking proper toilets or running water. They were often shiftless and stupid, many spent their money on drink and some on drugs, but their need was blatantly manifest to anyone who cared to walk down the long treeless streets and through the narrow courts. Born and bred in such shocking conditions, who could blame them for seeking at every opportunity the garish warmth of the public houses on almost every corner?’[8] At the same time, Helen’s memoirs noted the kindness of some of her neighbours who often shared what little they could and had sympathy for the Helen and her siblings who were clearly suffering. Helen highlights that her parents’ own snobbishness and inability to confront their own financial mismanagement was a barrier in the family’s integration into the neighbourhoods, as their hostility towards their neighbourhoods attracted a great deal of antagonism.

Helen’s memoirs help to us to appreciate the hostility and discrimination that the urban poor experienced, as her memoirs chart the awful encounters her family experienced trying to get support. Helen recalled ‘the studied rudeness with which every member of the family was faced whenever dealing with officialdom, by the labour exchanges, by the voluntary agencies working in the city, was a revelation to us. We began to understand, as never before, the great gulf between rich and poor, between middle class and labour.’[9] This perspective is particularly insightful if we are to understand the clashes and tensions between those who sought help and the government, charitable and welfare organisations that could provide assistance. As an example, it reinforces our understanding of how influential social class was in early-twentieth century Britain and how difficult it must have been to overcome economic barriers.

Helen’s family were, due to their affluent background, also able to benefit from the privileges afforded to the middle and upper classes. Her father eventually found employment when a policeman who had been at school with him recognised his tie and helped him get job as City clerk, which allows the family to rent a three bedroomed terraced house at a cheaper rent than the rooms they had been living in. Although it does not help when Helen’s parents again go overboard with lavish furniture on hire purchase, which is subsequently repossessed by the bailiffs. However, her parents’ upper-middle-class background did allow them to command some kind of power when confronted with child welfare authorities. Helen had been made to stay at home and look after the younger children, despite being desperate to go to school and it being compulsory until the age of fourteen. Her parents managed to evade the authorities until school attendance officer spotted Helen taking some of her younger siblings to school and subsequently visited her parents at home: ‘How they evaded being prosecuted and sent to prison for my long truancy I will never know. Perhaps their calm authoritative manners made even school attendance officers quail.’[10] Although they avoided prosecution, they were forced to allow Helen to attend school, which she managed for six precious weeks before they removed her as soon as she turned fourteen. Helen also notes that years later, she found out (presumably from one of her siblings that) ‘some people came from the child welfare authority and threatened to take us all into care’ and speculates that it had arisen from the doctor who identified her malnutrition whilst she was suffering from influenza, or her employers or the hospital that had treated her brother Brain for quinsy. ‘Whenever it was, my parents must have talked their way out of it. In those days, few would believe that neglect or Ill-treatment occurred in any but working-class homes; and once my parents’ original social status had been established there would be a tendency to believe anything they said.’[8] For me, Helen’s odd class identity – moving between middle-class and working-class worlds and identities – really adds to the richness of the perspective of her work. We have a strong sense of the powerlessness and deprivation suffered by the poor in 1930s Liverpool and the precarity and lack of support available to those in need, in contrast to the way that more affluent families could navigate and manipulate systems of power that were always stacked in their favour. These perspectives remain crucial as issues of poverty and social exclusion continue to exist and arguably take on greater urgency nearly a century after Helen was confronting the horrific realities of life below the breadline.

[1] Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, 168.

[2] Helen Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, 178.

[3] Helen Forrester, Liverpool Miss, 249.

[4] Helen Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey (London, 1974), 9.

[2] Bhatia, Passage Across the Mersey, 320.

[3] Bhatia, Passage Across the Mersey, 321.

[5] Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, 30.

[6] Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, 16-17.

[7] Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, 8.

[8] Helen Forrester, Liverpool Miss (London, 1986. First published 1979), 18-19.

[9] Forrester, Twopence to Cross the Mersey, 131.

[10] Forrester, Liverpool Miss, 175.

Further reading:

Helen Forrester,

Novels (years written are given where known)

Thursday’s Child (1959)

The Moneylenders of Shahpur (1964)

The Latchkey Kid (1964/5)

Liverpool Daisy (1979)

Three Women of Liverpool (1984)

Yes, Mama (1987)

The Lemon Tree (1990)

The Liverpool Basque (1993)

Mourning Doves (1996)

Madame Barbara (1999)

A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin (2003)

Non-Fiction

Twopence to Cross the Mersey (1974)

Liverpool Miss (1979)

By the Waters of Liverpool (1981)

Lime Street at Two (1985)

Biography

Robert Bhatia, Passage Across the Mersey (London, 2017)

Leave a comment