Content note – this article contains material relating to domestic violence, sexual abuse and childhood trauma.

Read more: “No more silly stuff?” Domestic Abuse, Poverty, and Family Life

Image: Woman’s Wrongs, 1874 by Joseph Swain. Image via Getty Images. Domestic violence was not always taken seriously by the police or the state and was viewed as an almost inevitable aspect of working-class life.

Sadly, the experience of domestic violence features heavily in some memoirs and is presented as a product of the severe poverty, hardship and poor living standards that so many experienced. Some accounts of the violence endured by memoirists are almost impossible to comprehend. Such as the life story of ‘Queen of Shoplifters’ Shirley Pitts who told her life story through a series of interviews with Lorraine Gamman. Pitts narrated the inescapable harm she experienced at the hands of her long-term boyfriend: ‘he really, really beat me up… (if) someone smiled and I smiled back, ‘ed just smack me right round the face, do you know? Yeah but I think he liked a Sunday fight with me, you know Sundays seemed to be his fighting day!’[1] Although the majority of victims were women and children, abused at the hands of their partner, husband or father figure, women also exerted physical violence within their families. Pitts admitted conducting horrific acts of violence herself against her boyfriend, often in response to the assaults inflicted by him: ‘he used to bash me and I used to think, “I’ll wait.”’[2] The levels of violence can be shocking and almost unreadable in these accounts and we need to take care not to sensationalise or use these stories without remembering the suffering behind them. Rather, these accounts of domestic violence can help us understand the difficulties faced by vulnerable women and children and the lack of support available, even in light of the provisions made by the post-1945 welfare state. Tommy Rhattigan’s memoir of his childhood in 1960s Hulme in Manchester, charts the severe poverty and neglect that he grew up in and in one instance recalled he and his brother Martin seeing pigeons eating mouldy bread ‘Always hungry, we snatched up a stale piece each and headed off down the street towards the Stretford Road, picking off the worst of the green mould as we went before eating it.’[3]

Rhattigan describes physical beatings from his mother and father and presents violence as part of his everyday life and intrinsic to the world he inhabited as a child. Describing his first experience of understanding someone else’s emotional pain, he recalled that ‘for the first time ever I realised pain came in many different forms and not just from the physical beatings we suffered at the hands of our parents, or strangers, or from the everyday cuts and bruises we sustained throughout our daily lives.’[4] In helping us understand and acknowledge the nature and scale of domestic violence experienced by some families in the mid to late twentieth centuries, these memoirists can help reveal the challenges and barriers current victims of domestic violence may continue to face and contribute to a greater awareness of the enduring impact of this abuse on vulnerable families.

Children playing in Manchester, 1950s. Image via Getty images. Tommy Rhattigan’,’s 1963: A slice of bread and jam describes his childhood in Manchester’s Hulme where he explored bombed houses and areas being demolished.

Reading the depictions of domestic violence and abuse in memoirs shows that by the 1960s and beyond, victims often articulated a sense of powerlessness as they often felt there was little in the way of social support or legal recourse. Andrea Ashworth’s moving memoir Once in a House on Fire, depicts her life in poverty in 1970s Manchester and the violence she, her sisters and mother were subjected to at the hands of two stepfathers. Ashworth’s father died when she was a toddler and her memoir charts the valuable support they received from other women, both those who lived locally and female relatives. Following a particularly brutal attack by her first stepfather, her mother chooses not to press charges but instead enlist the help offered by a close friend, Auntie Tamara: ‘More powerful than the police, our mother’s friend Auntie Tamara moved into a house down the next street, complete with daily visits from her brother who was big and black and broken-nosed: there was no way our stepfather would dare to come knocking now Uncle Clifford was hanging around.’ However, when her mother remarried and was subjected to further violence, the family lost much of the support as her mother’s friends grew increasingly frustrated that she would not leave him. Without this informal support, Ashworth described how she and her sister, Laurie, would try, unsuccessfully, to convince their mother to go to the police:

There was a police station tantalizingly near to our house; Laurie and I could see its blue sign glowing when we looked out from my room in the attic. But our mother refused to let us go over and grab an officer when things got out of hand. “They won’t do any good.” She was sceptical about their willingness as well as ability to help: “They think a woman dun’t get a slapping for nothing.”… The police had come round a couple of times, called by someone across the road, and had given our dad a mild ticking off, which only prompted him to hit our mother harder the minute the door shut behind them.’[5]

Ashworth’s contrast between the nearness of the police and her mother’s refusal to engage with them reinforces her sense of isolation and helplessness, suffering such horrendous abuse with little hope of finding a way to make it stop.

Housing in Manchester, 1976: Image via Getty images. Andrea Ashworth’s Once in a House on Fire charts her difficult childhood in 1970s Manchester.

This lack of support was especially true for vulnerable women and children who were also marginalised within society in other ways. The Nigerian writer Buchi Emecheta emigrated to London in 1962 and her autobiographical novel, Adah’s Story, charts the challenges leading character Adah faces during her first years in Britain, particularly regarding poverty and the racism she experienced that made it almost impossible to find suitable housing. It also depicts the unhappy marriage between Adah and Francis and the challenges Adah faced as a young migrant wife dealing with an abusive husband. Adah and her children managed to flee from her husband before realising she was pregnant with her fifth child. The novel explains how Francis pursued Adah and the children and forced his way into their new home. Emecheta depicts a horrendously violent confrontation between them:

What followed is too horrid to print. Adah remembered, though, that during the confusion Francis told her that he had a knife. He now carried knives with him. She tried several times to call for help, but could feel the life being squeezed out of her. She then heard people talking, banging the door which Francis had locked. But the landlord had guessed that Francis was Adah’s husband and, like most people, he didn’t want to interfere until a real murder had been committed. It was the old Irish man living on the top floor, Devlin was his name, who broke the door open.[6]

Emecheta highlights Adah’s vulnerability against Francis and his power and violence against a young, pregnant woman. Yet she also emphasises Adah’s aloneness and isolation, having emigrated to a city where she had known only Francis and although had become very popular with colleagues working at a library, had felt unable to share the problems she was experiencing. Adah is shown to be without support or friends that can assist and, even though, others can hear Adah’s scream, there is a reluctance to intervene.

A family dealing with homelessness in London, 1967: image via Getty images. The work of writers such as Buchi Emecheta helps us understand the poverty and hardships faced by migrants in 1960s Britain, particularly relating to the difficulty of obtaining housing.

At the same time, as Ashworth alludes to in her account, some women were reluctant to engage with the police, even when abuse had been widespread and affected children. Tommy Rhattigan’s 1963: A slice of bread and jam depicts his childhood as one of thirteen children living in Manchester’s Hulme as it was being demolished. Born in Ireland to parents of Travellers heritage, depicts a life of poverty and neglect as he and his siblings often avoided school, had little to eat, and spent their time stripping abandoned houses for copper wire, coal and anything else worth money, to fund their parents’ drinking. Rhattigan and his siblings were eventually removed from their parents after his father is imprisoned for sexually abusing his sisters. He describes his mother’s furious response when the sisters’ complaint to the police came to light, as Rhattigan recalled: “Yea’ve no rights talking about yer Father like this!” said Mammy. But the venom in her own voice was lost as she searched for the words to thrown back at my sisters. “He’s clothed yah – he’s fed ya! He’s…” “used and abused us in every fuckin’ way that he could!” spat Mary. “Get out of my house yah pair of feckin’ whores! Get out!”’[7] His mother insisted that Tommy and one of his other brothers should lie to the police in order to exonerate their father and secure his release, although this was ultimately unsuccessful. The father’s conviction led the younger children to be placed in care, whilst Tommy and his closest brother Martin were sent to approved schools and his family were never united again. This outcome may help to explain why some women feared engaging with the police as it could lead to the removal of children and to the kind of state intrusion that they feared. In Rhattigan’s second memoir, he explains that his mother had occasionally articulated a sense of powerlessness against his father, claiming ‘Jaysus, I can’t stop him drinkin’ an’ carryin’ one all the while.’ He explained that he had some sympathy for her as she was uneducated and illiterate but struggled to forgive her lack of intervention when he was being subjected to his father’s violence.[8] This account suggests there may have been a sense of acceptance around abuse as part of wider patriarchal gender roles and the belief that the father figure’s role as the breadwinner.

Certainly, it was more difficult for marginalised women experiencing abuse to bring about a change of circumstances or to use the powers of the state to support them and their families. Returning to Buchi Emecheta, Adah’s Story, we are told that Adah decided to take legal action against Francis following his near fatal attack on her. Emecheta explains: ‘She was mot suing for maintenance, she did not even know if she was entitled to any. She simply wanted her safety, and protection for the children.’ However, Adah chose not to call for evidence from the doctor who treated her after the brutal attack by Francis, despite the doctor offering to do so. Adah was worried that, if she did so, Francis would be sent to prison ‘and what good would that do to her?’[9] Francis, in contrast, provided a ruthlessly self-interested court appearance and attempted to convince the judge that Adah’s injuries were a result from falling. For Adah, the court case was a turning point as she realised the importance of her own self sufficiency and her commitment to caring for her children, against the lack of support she received from her husband or from the state.

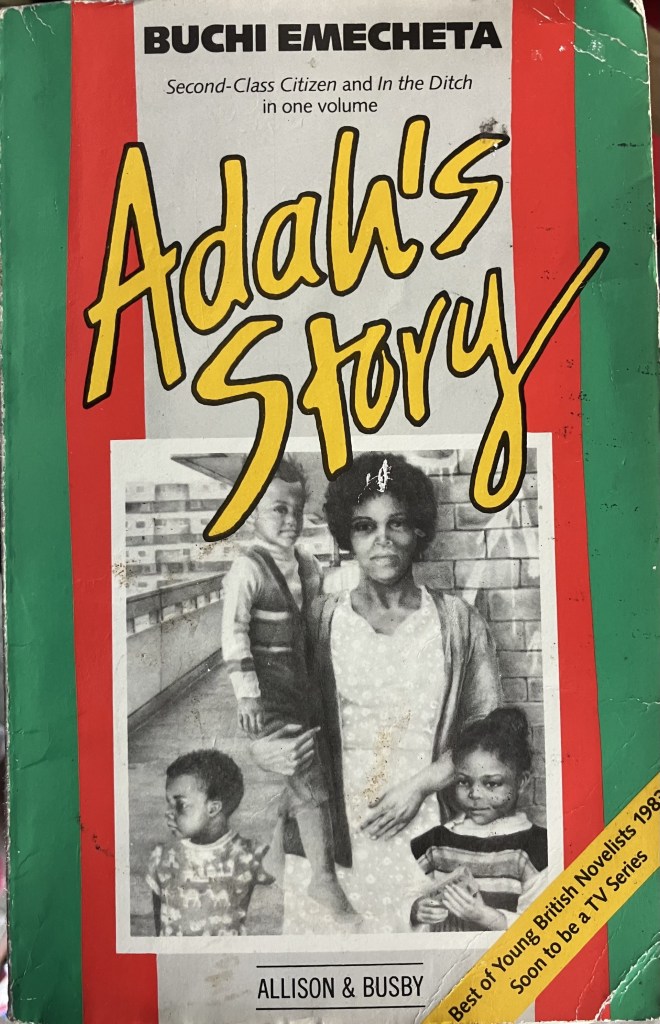

Buchi Emecheta, Adah’s Story – brought together her two autobiographical novels, Second-Class Citizen and In the Ditch in one book.

The difficulties faced by vulnerable women like Adah were, unfortunately, by no means unique. Considering that domestic violence and abuse is a prominent theme in some memoirs however, it was not necessarily condemned or pursued in police prosecutions. Perhaps because it was seen as a widespread and associated with poverty and alcohol, the police did not always address it seriously and it was often allowed to go unchecked. Andrea Ashworth describes the lack of support she and her family received in light of the ongoing domestic abuse being carried out by their second stepfather. Ashworth recounts a particularly violent incident: ‘I was certain my dad was going to do my mother in.’ Urgently running to the nearby police station, she recalls the frustration she felt when she was not taken seriously, as ‘two constables took ages fastening shirt cuffs, buttoning jackets, stapling helmets under chins, before they strolled up the road behind me.’[10] At home, her stepfather tried to charm the police and denied any trouble and her mother was reluctant to talk: ‘Our mother was too crushed to give anything away when they asked her what had been going on. But this time I found the nerve to speak up about the punches and kicks and the way our dad had been throttling our mother when I ran to fetch help.’ The police then asked to speak to her stepfather in private and you can almost hear the disbelief and sense of hopelessness in Ashworth’s prose as she recalled Andrea ‘expecting to see Dad’s head bowed over handcuffed wrists. Instead, he looked almost chipper, acting pally with the officers. They smiled at our mother as they reached for the door: “No more silly stuff?”[11] Ashworth’s protests at this dismissive police response was met with patronising comments that she should not be so hysterical. As with Adah’s Story, Ashworth shows this moment as a turning point and her mother and stepfather part ways, before she embarks on her own path to freedom through education.

Women on the march in Liverpool in protest against violence, 1979. Image: Getty Images. Feminist campaigns in the 1970s focussed on the problem of violence and led to the foundation of important charities such as Refuge and Women’s Aid.

These memoirists and writers have shared such moments of personal pain and anguish and have explored some of the most horrific moments of their lives. Their work has provided a sense of the relentlessness and insidious form that domestic violence and abuse can take and the difficulties in obtaining support and intervention in the 1960s and 1970s. These accounts shows that in post-war Britain traditional gender roles, particularly about masculinity and fatherhood, and attitudes to the poor made it difficult for victims to seek help. It brings home the important work undertaken by women’s welfare charities and especially the creation of refuges for women fleeing violence, such as Refuge and Women’s Aid, which were both founded in the 1970s. Although approaches from the police and from welfare agencies have moved on since the 1970s, these accounts also describe the harms caused by domestic violence and abuse beyond the act themselves. The links between poverty, poor housing and domestic violence come through very strongly in these accounts and shows how these problems were significant obstacles in helping victims leave abusive scenarios. They also remind us that how we think about domestic violence and abuse has changed in recent years as concepts such as coercive control and gaslighting are relatively new, for example. These voices and their bravery in providing these intimate accounts can help to forge more sympathetic understandings and greater awareness of the dangers that may continue to lurk behind closed doors.

[1] Lorraine Gamman, Gone Shopping: the story of Shirley Pitts, Queen of Thieves (London, 2012), Appendix 114.

[2] Gamman, Gone Shopping, Appendix 114.

[3] Tommy Rhattigan, Boy Number 26 (Mirror Books: London, 2019), 8.

[4] Tommy Rhattigan, 1963: A slice of bread and jam (Mirror Books: London, 2017), 170.

[5] Andrea Ashworth, Once in a House on Fire (Picador: London, 1998), 166 and 280.

[6] Buchi Emecheta, Adah’s Story (Allison & Busby: London, 1983), 142.

[7] Tommy Rhattigan, 1963: A slice of bread and jam (Mirror Books: London, 2017), 259.

[8] Tommy Rhattigan, Boy Number 26 (Mirror Books: London, 2019), 44.

[9] Emecheta, Adah’s Story, 143.

[10] Ashworth, Once in a House on Fire, 282.

[11] Ashworth, Once in a House on Fire, 282.

Leave a comment